|

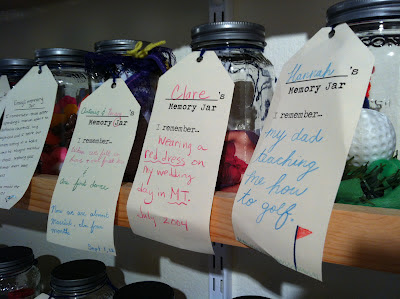

| Visitors bond and bridge through participatory experiences at MAH. |

There were times when coordinating a fire art festival while researching social

capital theory made me want to burn my computer. But, overall I felt

overwhelmingly fortunate to be in a job, a museum and a community that I loved

and furthermore to be afforded the valuable time most of us do not have to

devote to further researching, thinking about, reading and discussing the theories

that comprise the foundation of my work.

I chose to focus my thesis on Community and Civic Engagement

in Museum Programs. The purpose of my

thesis was two-fold:

- To research and analyze community and civic engagement practices, methods, theories and examples in other museum programs.

- To apply the results of my analysis to produce a community-driven program design specifically for implementation at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History (the MAH).

Assess and Respond to Community Assets and Needs

If you want to activate community engagement in your

programs, you first need to work together with your communities to determine

their diverse needs, assets and interests. This can be accomplished through a

variety of feedback methods conducted both inside and outside the museum. Deeper community relationships through focus

groups or community advising committees can further help museums connect with issues

relevant to their communities while also hold the museum accountable for their

responses.

Two exceptional examples of community committees stand out:

one long standing, The

Community Advisory Committees of The Wing Luke Museum of the

Asian Pacific American Experience and one emerging, the Creative

Community Council of the Children’s Creativity Museum. Both emphasize museums reaching out into the

community to support, understand and experience what the community is already

doing. They stress community engagement should be an asset- over needs-based

approach. It’s not solely about how museums can serve communities but rather

what are the communities’ resources, knowledge and interests that can inform

museum practice? Furthermore, how can museums and communities work together to

share strengths in the community?

Museum programs need to then actively respond to their

communities through a variety of ongoing discursive, collaborative and inclusive

formats that address needs and assets but also invite communities to be active

participants in this process.

At the MAH

Our first program goal is to meet the needs and assets of

our community as defined by our community.

We seek to understand this by listening to and developing ongoing dialogues

with a range of community members. We attentively respond to requests and

purposefully use different modes of feedback to inform program design from our

comment board, social media outlets, conversations and observations both inside

and outside the museum, creative feedback at events such as our Show

and Tell Booth and online visitor surveys specific to our programs. We continuously and actively respond to

requests as well as invite people to be a part of our programs.

We also formed a Creative

Community Committee (C3), composed of a diverse range of

multigenerational community representatives from social services, the arts,

business, education, the city, technology and our board of directors to provide

a multitude of perspectives and expertise.

C3 meets bimonthly to help us understand and brainstorm ways the MAH can

collaboratively implement and address the needs and assets of the vast array of

communities in Santa Cruz County.

Build Social Capital

A crucial theory in community engagement through museum

programs is social capital theory, best defined by Robert D. Putnam, who has

written extensively about social capital in American society in his book, Bowling

Alone. Putnam defines social capital as “connections among individuals-social

networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from

them.” Social capital has two main

forms; it should gradually and increasingly encompass both distinct forms of

bonding and bridging to create healthier, wiser, more connected, economically

and socially sustainable communities.

Bonding social capital refers to networks that bring people

together with common interests to strengthen relationships in preexisting

groups.

Bridging refers to an inclusive and outward looking form of

linking different and diverse individuals and groups together to form new

relationships.

Museum programs can be designed to further bond similar

groups together such as families and friends in family workshops such as the

Dallas Museum of Art’s First

Tuesdays. Museum programs can also bridge different groups that

might not typically interact such as the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum’s

Educational Residential Centre, which designed a program specifically to bridge

children of two groups engaged in social conflict, Catholics and Protestants.

Co-created programming that represents the complex range of

voices in communities, offers platforms for communication, collaboration and

shared experiences that can enrich preexisting relationships while also offer a

space for new relationships to form and strengthen. An example of this is The Portland Art

Museum’s partnership with the faculty and students in Portland State University’s

Art and Social Practice Department for their annual Shine a Light

program. The program is an experimental

playground that bridges artists, students, chefs, comedians, hairdressers,

bartenders, dancers, wrestlers and even tattoo artists to produce a community-led

event. Collaborative programs with

diverse groups bring in a variety of visitors causing new audiences to interact

and connect.

At the MAH

Our second community program goal is to build social capital

by strengthening community connections with our collaborators and

visitors. This is a continual process of

bonding within preexisting groups and bridging between groups and individuals

who might not usually interact.

Our programs bond our collaborators by closely co-creating

programs with community organizations which strengthens their individual

internal connections and their relationship to the MAH. For example, the MAH’s Poetry

and Book Arts Extravaganza event partnered with Book Arts Santa Cruz and Poetry Santa Cruz to collaborate

with 61 talented book artists and poets. Evaluation surveys showed that Book Arts Santa

Cruz members felt their bonds were strengthened as they connected with members

in a collaborative capacity that increased group dialogue and stimulated a

sense of pride, identity and vision around their work as a group at this event.

|

| Cardboard tube orchestra at Radical Craft Night. |

Sometimes we purposefully bridge distinct groups as well

such as middle-aged women from local knitting groups with young college

students interested in street art to yarn bomb our stairwell for Radical

Craft Night. The MAH’s

historic Evergreen

Cemetery brings together the Homeless Services Center and MAH

volunteers or the local rugby team to collaboratively restore the

cemetery. We are constantly looking for

new meaningful opportunities to bridge groups and individuals in our

programs.

Design to Invite Active Participation

Participatory design can be one of the most effective vehicles

for developing relationships, building social capital and engaging with

community members in museum programs.

Implementing participatory activities and constructivist learning

theories allow the learner to actively experiment cognitively and physically,

individually and socially, and to collectively build meaning and knowledge.

Participatory programming highlights alternative narratives, activates

communities and reverses the role of the visitors from consumer to producer,

which in turn engenders more connected and active communities.

The value of participatory experiences is epitomized in FIGMENT, a

free, creative, participatory, non-profit, community art event. This participatory event led by emerging artists

from all backgrounds, engages communities by encouraging a culture of making,

doing, creating and collaboration rather than spectatorship.

The Denver Art Museum has been leading the way with dynamic

programs such as Untitled, which offers

a variety of non-traditional encounters with art and the museum through

participatory, multidisciplinary activities led by Denver’s creative

community.

At the MAH

Our third community program goal is to invite active

participation by offering opportunities at events for visitors to have

meaningful, hands-on, cultural experiences in which they act as contributors and

co-creators, not just consumers. We

scaffold levels of participatory experiences at events that are

intergenerational, multidisciplinary and appeal to different types of learners.

We give visitors a new skill to claim rather than a product and work intensely

with our collaborators to insure active participation in their activities.

All of our events require some level of participation. Sometimes

that results in an artist-led cascading collaborative sculpture of 475

visitor-made scrap metal fish. Other

times it’s a collaborative collage animation workshop, a black light art

activity with red lentils, dodge ball, recording songs to send to loved ones,

writing haikus for strangers or an urban history scavenger hunt on bikes.

|

| Artists from different worlds, brought together through Street Art Night. |

Final Thoughts

These

are certainly not the only components that constitute successful community

engagement in museum programs but they are central for MAH programs and for our

community. This summer, at our Street

Art Night, when I saw a young graffiti artist learning how to knit from a

woman in her sixties and then taught her how to spray paint or at Experience

Metal, when a motorcycle repairman learns how to operate a new tool from an

art bike welder or when families work together to create their own cardboard

neighborhood or when two individuals who met at one of our events team up to

collaborate- it allows me to see first hand the gradual impact of our goals on

the community and makes me realize all those late nights spent writing my

thesis were completely worth it.

Stacey will be responding to your questions and comments on this post. Enjoy her thesis, share your own example, have a meaty conversation.

Stacey will be responding to your questions and comments on this post. Enjoy her thesis, share your own example, have a meaty conversation.

From 2006-2019, Museum 2.0 was authored by Nina Simon. Nina is the founder/CEO of

From 2006-2019, Museum 2.0 was authored by Nina Simon. Nina is the founder/CEO of